About Integral Motion :

From the realm of transpersonal psychology

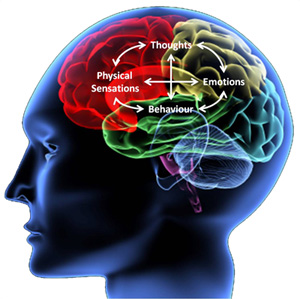

Integral Motion is a body mind and soul practice that works at the 5 levels : Physical , Energetic , Emotional , Mental and Spiritual .

It’s a unique blend of ancestral and modern technics based on movement , breathing , powerful evocative and rhythmic music and different states of consciousness .

Different technics from 3 tool boxes are learnt before , then practised during a 2 hour musical journey . You can experiment with it to produce results at every levels

-Pure Motion : releases tensions , detoxifies and energize the body .

-Motion meditation :calm and clarify the mind promoting emotional balance.

-Mystic Motion : Using ancestral and modern technics to naturally expand consciousness .

The use of a blind foil or bandana “rewires” the perception and helps entering the music at a deeper level .

http://www.facebook.com/integralmotionhk/

About Holotropic Breathwork :

Holotropic Breathwork is a powerful technique for self- healing and self-exploration allowing for greater self- understanding, expansion of self-identity and access to the roots of emotional and psychosomatic challenges one might face.

Holotropic Breathwork comes from the Greek words ‘holos’ (whole) and ‘trepein’ (going to) meaning moving towards wholeness.

Based on extensive research in psychiatric, psychotherapeutic and spiritual settings it has been developed by the psychiatrist and psychotherapist Dr. Stanislav Grof and his wife Christina Grof.

It involves a combination of breathing, evocative music, focused energy release work and integration through art work and sharing. However, the healing and transformation powers develop solely through ones connection with the breath diving deep into non-ordinary states of consciousness such as meditative and mystical experiences allowing deep healing and self- empowerment.

http://www.facebook.com/holotropicbreathworkhongkong/

12 Things You Should Know About Holotropic Breathwork™ – by Martin Boroson

- with Jean Farrell, Nienke Merbis, and Dara White

Many people know Dr. Stanislav Grof as a pioneering researcher in the clinical use of LSD in psychotherapy. Others know him as the founder, with Abraham Maslow, of the movement known as transpersonal psychology. He is, in the opinion of Ken Wilber, “arguably the world’s greatest living psychologist.” Many people have also heard of the technique that he developed with his wife, Christina Grof, called Holotropic Breathwork™.

Holotropic Breathwork™ refers to a process in which deep, fast breathing, in a supportive context, is used as a catalyst for the experience of a non-ordinary state of consciousness (NOSC). This state of consciousness is thought to be inherently healing and evolutionary, bringing to the surface any issues that need addressing and helping the client to resolve them in a creative way. Holotropic Breathwork has been called “industrial strength meditation.”

In a Holotropic Breathwork workshop, clients work in pairs, with one as the ‘breather’ and the other as the ‘sitter’. The breather lies down on a mattress, while the sitter ensures that the breather is physically safe and supported during the session. The instructions for the breather are simply to breathe deeper and faster, keeping eyes closed. This gradually brings on a non-ordinary state of consciousness—like a vivid dream—and the breather simply trusts the wisdom of whatever emerges. Breathers are free to make any motion, move into any posture, or make any sound they wish. The experience is supported by music, which begins with drumming or similar ‘driving’ music, reaches an emotional crescendo, transitions to ‘heart’ music, and finishes with meditative music. Sessions are scheduled to last for three hours. Later that day, or the next day, the breather and sitter swap roles. Sessions are followed by two optional activities: expressive artwork and small group sharing. Facilitators are always present to explain the method, create the safe setting, support the process, and work with people if they experience any difficulty.

1. Does Holotropic Breathwork involve drugs?

No.

Grof was one of the earliest and most respected researchers into the clinical use of LSD. A Freudian analyst and psychiatrist, he became convinced that LSD had therapeutic value as a catalyst for the healing potential of the unconscious. Grof conducted LSD treatment at the Psychiatric Research Institute in Prague from 1960 to 1967, and continued this work at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He worked with psychiatric patients, cancer patients, and drug addicts, as well as with artists and scientists who were curious about the deeper dimensions of their minds.

At the time, there were a variety of ways of working with LSD, but Grof’s method was remarkable for the use of a very safe setting and its inner focus. This involved the patient lying down with eyes closed, listening to music, and being attended at all times by two clinicians. Thus the focus was on inner experience, rather than interactive or psychodynamic experience, and on accessing the unconscious experientially, rather than intellectually, verbally or analytically. Grof observed and reported remarkable therapeutic benefits for his patients from this process. Furthermore he realized that these states of consciousness were not nearly as non-ordinary as they seemed: most pre-industrial cultures had some culturally-sanctioned way to enter these states, periodically, to promote healing or find wisdom, using things like drumming, natural psychedelics, meditation, or fasting as the catalyst.

Grof’s clinical research into LSD was extremely promising, but because of the street use of the drug, and its promotion by less sober figures such as Timothy Leary, the non-clinical use of the drug was banned in the U.S. in 1967, and clinical research ended in 1975. So he turned his attention to other methods of inducing a non-ordinary state of consciousness, and settled on the use of deep, fast breathing. This is the basis of Holotropic Breathwork™. Although Holotropic Breathwork has some of the similarities, in setting and intention, of Grof’s work with LSD, a Holotropic Breathwork session absolutely does not involve drugs. As with many forms of yoga, it is powered by simply breathing, at a rate controlled by the client.

2. Is the facilitator a healer?

The primary principle of Holotropic Breathwork is that healing comes from within the client. In the holotropic model, this is taken to an unprecedented level of trust. Facilitators are not considered to be healers or even therapists. Rather, they are more like mid-wives, there to support a process that has an inherent wisdom. Facilitating a Holotropic Breathwork workshop is intense practice in ‘not knowing’. I recall Grof saying that the reason the training to be a facilitator takes a minimum of two years is that it takes at least two years to realize how little you know.

Grof believes that there is an inner ‘radar’ function in the psyche that, when given the opportunity, can choose the most relevant experience we need, in that moment, for our evolution.[i] No one can know what that experience is, in advance. For example, consider a client locked in a pattern of anger at her mother: what would be the best prescription for her? A bio-energetic therapist might encourage her to express her rage. A Buddhist teacher might encourage her to practice compassion. A Jungian might encourage her to dialogue with the image of her anger. A Kundalini yogi might encourage her to channel the anger into a higher form. But a Holotropic Breathwork facilitator would say simply, “keep doing the breathing and find out what is emerging for you.” The answer is specific to the client and to the time.

It is always tempting to think we ‘know best’. This is particularly true for anyone in the helping professions. But the Holotropic Breathwork facilitator is trained in not-knowing. Of course, many people have great gifts in their chosen modalities, whether cranio-sacral therapy, reiki, bioenergetics, psychodynamic psychotherapy, or cleansing auras, but in a holotropic workshop these would never be applied to a client’s process. To ‘heal someone’ is a beautiful thing, but in the context of a Holotropic Breathwork workshop, it would be considered an abuse of power. Each participant should leave a Holotropic Breathwork workshop feeling personally empowered: having discovered that he himself has answers within—not that so-and-so is ‘a great healer’. The Holotropic Breathwork facilitator is not expected to do the healing and should not promote the idea of being a healer. The facilitator of a Holotropic Breathwork session is there to help, support and encourage clients to find their own way.

Many clients do come to a Holotropic Breathwork workshop wanting ‘to be healed,’ or with an unconscious need to find a guru. This can be a trap for both client and facilitator. But a good facilitator will resist that projection, and gently encourage the client to look for an answer within. Of course, some facilitators do have a strong healing presence, or may be gifted in ‘seeing’ or understanding. But all good Holotropic Breathwork facilitators should keep that firmly in check: the practice of being a facilitator is of not-knowing, and giving space to individuals to find the answers themselves.

3. Is Holotropic Breathwork is a kind of shamanism?

There are many ways in which Holotropic Breathwork resembles shamanism. As in shamanism, participants in a Holotropic Breathwork workshop go on a journey into a non-ordinary state of consciousness to find healing. Music is played to support this journey. But there are many differences between Holotropic Breathwork and shamanism. First, there is no roadmap for the Holotropic Breathwork journey: participants are not asked to imagine an entrance to a shamanic world, and don’t begin their holotropic journey with an intention to work on a specific problem or question. It certainly makes sense to look for a spirit guide or power animal at a shamanic workshop, for these are typical features of the shamanic world, but to do this in a holotropic session would constrain the process. In a holotropic session, the whole world of possible spiritual experience, from any tradition (and from no tradition), is available to each client.

One of the most remarkable features of Holotropic Breathwork is that people can have so many different kinds of experiences, and are free to interpret them differently, without any specific language or worldview. I have seen Christians having Buddhist experiences, and Hindus having Christian experiences. I have seen atheists have shamanic experiences and shamanic practitioners have Sufi experiences. (I even remember a Catholic priest having a Christian experience, and expressing surprise and delight to discover what his faith was really about.) I have also seen people have experiences that seem to pull from many different traditions at once, and have seen some people have experiences from no tradition yet identified. So although Holotropic Breathwork has many features that are similar to shamanism, it is much bigger and broader. In this sense, it is a truly post-modern practice[ii].

4. Is Holotropic Breathwork addictive?

I have certainly seen some people seem to get hooked on Holotropic Breathwork. But we have to be careful here. Many people come to Holotropic Breathwork as a last resort, or when they are in a psycho-spiritual crisis. In such cases, an intensive period of inner work is not just desired but essential for them. They may want or need to give their lives over to their inner process for a period of time. For other people, a holotropic workshop may be the only place they have found in which they can truly be themselves, and where they can give expression to some very big energies they have been struggling with. Then there are other people, like myself, who consider Holotropic Breathwork a spiritual practice, and try to do it at least a couple of times a year, much as one would a meditation retreat. But although I have seen plenty of people practice Holotropic Breathwork intensely for a period of time, and some people who seem perhaps too attached to it for a while, I have seen no one ‘addicted’ to it.

There is probably not a single practice that, in the hands of an addict, can’t be used addictively. Holotropic Breathwork is definitely not appropriate for people who are actively addicted to anything (whether a drug, alcohol, food, or behaviour), as it tends to bring to the surface just that material that the addict is trying, through the addiction, to suppress; this increased conflict could increase addictive behaviour. But once an addict is in recovery, Holotropic Breathwork can be extremely healing, helping the recovering addict work through the suppressed material, and perhaps discover the deeper patterns that gave rise to his addiction.[iii]

5. Is there a prescribed ‘order’ of experience?

I have seen many newcomers to Holotropic Breathwork arrive at a workshop with fixed ideas about what they have to experience or will experience, as if they’d been given instructions by their therapist. (One person even arrived with a map of his body, drawn by his therapist, showing me where his ‘stuff’ was.) But in Holotropic Breathwork, there is no prescribed order of experience, and no way to predict what will emerge. Facilitators stress over and over again: let go of your agenda and be willing to be surprised. The inner healer will select the issue you will explore, the healing you will experience, and the lesson you will learn.

There is also a common misperception that clients must first clear personal trauma, then work through birth trauma, and then, if they’re lucky, might have a transpersonal experience. This is an understandable misunderstanding of Grof’s work, for he did suggest this as the general order of discovery in a holotropic process. However on a case by case, session by session, basis, it doesn’t work like that. I have seen many people have very powerful spiritual experiences in their very first session: these experiences may give them the incentive to continue, an overview of their process, or the tools they need to continue. I have seen many people whose first sessions are entirely transpersonal, and this might continue for many sessions, until they realize that the next edge for their growth is in their personal life, or in their personal history.

Interestingly, many sessions present many levels of the psyche at the same time, in a fascinating, holographic way. And as with dreams, each session can contain a prelude or hint of things to come. I remember one participant, a devout vegetarian, having a holotropic session in which the image of a Big Mac appeared in his mind, fleetingly, much to his amusement. In his next session, several days later, he had a full-blown transpersonal experience in which he experienced himself as a lion, hungrily devouring the raw meat of a just-killed animal.

I have come to believe that Holotropic Breathwork simply brings up exactly the experience we need right now, in the moment, from whatever level of consciousness. Whether this is a ‘therapeutic’ experience or a ‘spiritual’ experience is irrelevant. Whether it seems to be from the past is also irrelevant. Whether it is literal or metaphoric also doesn’t seem to matter much. What matters most is simply having that experience, that day. The session gives you a glimpse of the archetypal structure of the present moment, and brings you, very efficiently, to the next stage of your development.

6. Does Holotropic Breathwork require bodywork?

Holotropic Breathwork facilitators are trained to help participants with a form of support that is sometimes called, and often confused with, bodywork. Increasingly, however, this is called “Focused Energy Release Work” rather than “bodywork”. It is available to clients, if they request it, during a session or at the end of a session. It is used requested by participants when they feel stuck, ungrounded, or perceive that their session hasn’t completed.

Most participants complete their sessions without needing any such help. But if someone does want help, a facilitator will respond creatively and empathically to whatever the client asks for. More often than not, this means simply placing a hand gently on the shoulder for encouragement. Sometimes a facilitator will suggest that the client amplify what is already happening. This could be physical amplification but could also be expressive amplification. It might mean simply encouraging a client to vocalise a sound, or explore an image, that she is already experiencing. A client might also want physical resistance for a particular gesture in order to intensify the feeling in it. But this physical resistance does not involve doing something to the client, and it is never ever intended to overwhelm the client. It is simply meeting the client where she is, and encouraging her to go a bit further, if she wishes.

Unfortunately, I have seen some therapists, not trained by Grof, do some interventions in work with non-ordinary states that appalled me, so let me be very clear: A Holotropic Breathwork facilitator would never ever physically intervene in a session without the client’s permission—unless there were imminent danger that the client would hurt himself or someone else.

7. Does Holotropic Breathwork cause you to have an out-of-body experience?

It is certainly possible to have an out-of-body experience in a Holotropic Breathwork session. Most Holotropic Breathwork sessions, however, are exceptionally embodied. In fact, this may be one of the most valuable aspects of Holotropic Breathwork. Because the breather is lying down, on a mat, with someone nearby to ensure that he won’t get hurt, it is possible for his body to do whatever it needs to do. This is quite a different injunction, for example, than in a meditation retreat, where the exact physical posture for practice may be prescribed. In a Holotropic Breathwork workshop you can express yourself physically in just about any way imaginable. More to the point, you can allow your unconscious to express itself physically, in any way it wants to. Thus participants can have fully embodied spiritual experiences, quite idiosyncratically expressed. I have seen no practice that marries the transcendent and the immanent, or the spiritual and the physical, so effectively.

8. Do participants leave the workshops ‘ungrounded’?

After any dramatic experience, there is a risk of being ‘ungrounded’. People returning from an ashram or meditation retreat, and even from a therapy session or massage, can be ungrounded. Deep experiences are often unsettling, and it can take some time to integrate such experiences with ordinary life. This is why Holotropic Breathwork sessions are usually offered in overnight retreats, and at minimum in day-long retreats. A residential set-up helps people go into the experience more deeply, and gives them more time to complete the experience. Good facilitators make sure that people are sufficiently grounded before they leave a workshop, and are available to help them after the workshop if necessary. Holotropic Breathwork facilitators will often refer people to an appropriate therapist for continued support and integration of their experiences (and many therapists refer clients to Holotropic Breathwork as an adjunct to their therapy).

In some ways, Holotropic Breathwork actually offers a superior form of grounding. Facilitators commit to staying with a client until the client has reached a reasonable level of closure with the session. Most people finish their session within 2 to 3 hours, but facilitators understand that the ending of a session cannot be imposed arbitrarily: each session has its own internal logic. (On rare occasions, I have seen some facilitators, including Stan Grof, stay with someone all night.)

More to the point, there is no one ‘method’ of closure. Facilitators work with each client, if necessary, to ensure appropriate closure. Before trying Holotropic Breathwork, I had had many deep experiences at the hands of therapists who didn’t understand this. They ended my sessions at a time of their choosing, or at our pre-arranged time, by using a guided visualisation, a closing ritual, or simply pointing out the time and subtly encouraging me to get up. While this is understandable from the point-of-view of the schedule, it may have absolutely nothing to do with the needs of the client, and it is potentially damaging to the innate wisdom of the client’s psyche. Why invite a process to begin, in a spirit of trust, only to constrain it arbitrarily?

This is not just a matter of time. A Holotropic Breathwork facilitator encourages each client to find the unique symbol (i.e. expression, realization, image, or need) that completes his journey and helps him feel ready to return. It was only when I encountered Holotropic Breathwork, properly facilitated, that I was able to find authentic closure on certain issues, finding the unique answer that my own particular psychological predicament required. I no longer had to ‘hoist myself back’ to ordinary life to meet the demands of others, but instead learned how to find my own way back, in a way that felt authentic.

Sometimes, of course, a journey cannot be completed in one session—some journeys last lifetimes—but there can at least be appropriate closure on that particular leg of the journey. However, shutting down a session prematurely is like asking Jason to return home without the Golden Fleece because his dinner is getting cold. To allow people find their own way back is both more empowering, more ethical, more satisfying, and ultimately, much more efficient.

9. Does Holotropic Breathwork induce an “altered state of consciousness”?

The term ‘altered states’ was widely used in the early days of the transpersonal movement, but with its suggestion of abnormality or pathology, it has become less and less favoured. The term “non-ordinary states of consciousness” is preferred, as it does not judge these states positively or negatively. Grof also tends to call these states of consciousness simply “holotropic”, which means “moving toward wholeness.” In other words, Holotropic Breathwork simply opens us to a state of consciousness that helps move us toward wholeness.

In recent years, I have heard some people use the term “extraordinary states of consciousness”, which suggests the beauty and possibility of such states. Personally, however, I have come to believe that such states of consciousness—like dreams—are always present; they are only extraordinary if we aren’t already aware of them. I believe that the symbolic world is actually happening all the time, but we are just too ‘awake’ to notice. My current understanding of Holotropic Breathwork is that it simply brings us into deeper dimensions of the present moment, revealing a bit more of the colourful spectrum that is reality, right now.

10. Is Holotropic Breathwork violent?

From years working as a therapist and a Holotropic Breathwork facilitator, and from my own personal journey, I have learned that there are violent feelings, desires, and reactions in each of us. The question is to what extent we know about these and can work with them skilfully, as opposed to being surprised by them, projecting them onto others, or acting them out in the world.

Certainly Holotropic Breathwork allows people an unrivalled opportunity to work with their own anger and rage. Clients feel confident that they will not hurt anyone, including themselves. They are permitted to make as much noise as they wish. Thus they are really free to vent their violent feelings. Anyone wandering into a workshop, without understanding this, might assume that the work is violent. But I believe that what is happening is just a dramatic enactment of the interior of the human psyche, which of course includes violent feelings. Just because people can experience violent feelings in a holotropic session doesn’t mean that the process is violent. Most people who attend a Holotropic Breathwork workshop have, in my opinion, made a decision to face the truth of themselves, including their shadow, so that they can be more peaceful in their ordinary lives.

Certainly, engagement with anger can be challenging for people. Many people, after years of being depressed, or disconnected from their anger, discover so much anger that they need to learn anger management techniques, or take up a sport, just to process or handle this upsurge of feeling. But while this upsurge of anger can be challenging in the short term, in the context of healing, it is progress.

A Holotropic Breathwork facilitator would never make the expression of angry feelings an agenda for a client. The expression of angry feelings is merely one of the many possible experiences that might emerge in a session. Indeed many Holotropic Breathwork sessions are peaceful, joyous, or playful. Having co-facilitated nearly 10,000 Holotropic Breathwork sessions, I have certainly seen a lot of anger, but I have seen even more sadness, grief, vulnerability, gentleness, wisdom and wonder.

11. Is Holotropic Breathwork just about reliving trauma?

One of the most common misperceptions about Holotropic Breathwork, particularly in Ireland, is that it is only about recovery from trauma. This may be due to the fact the bulk of Holotropic Breathwork done in Ireland was in the 1990s. (And some therapists, not trained by Grof, were doing their own version of it in the 1980s). This was a time of great transition in Ireland. The reality of physical and sexual abuse, at the hands of parents, teachers, and clergy, was just beginning to become known. Therapists were helping clients process this trauma at a time when the culture was not very supportive of the truth of that trauma. And the people who came to Holotropic Breathwork workshops were often those who were particularly depressed, ‘stuck’, or emotional. They were often those people who had suffered the most severe trauma. They were referred to Holotropic Breathwork workshops by their therapists because they were not making any progress, or because the therapists couldn’t handle the intensity of the process. All of this has skewed the perception in Ireland of Holotropic Breathwork.

Holotropic Breathwork is practiced by people in recovery from trauma and also practiced by people who have no known trauma. I know of a Zen teacher who refers people to Holotropic Breathwork when their meditation practice gets stuck. I have seen Holotropic Breathwork as a very effective partner with other forms of personal development. It has been used in the context of leadership development, interfaith dialogue, and gender reconciliation. The point is that Holotropic Breathwork is a modern way for us all to explore the deepest dimensions of ourselves: sometimes that involved healing what happened before, and sometimes that means discovering what is happening beyond. But always, it means touching what is truly happening right now.

Yes, Holotropic Breathwork does seem to offer people the possibility of recollected memory and an extraordinary opportunity for catharsis. And it is often a history of trauma, or the onset of symptoms from a trauma, that drive an individual to a path of self-discovery. But Holotropic Breathwork is not primarily about trauma. Nor would a Holotropic Breathwork facilitator encourage a client to ‘believe’ a recollected memory as fact, for two reasons. First, it is always up to the client to interpret the experience. Second, Holotropic Breathwork sessions, like dreams, usually contain a mixture of elements, both biographical and symbolic, which can be very hard to separate. This is not to say that a recollected trauma did not happen, merely that it is not the role of the Holotropic Breathwork facilitator to set an agenda or interpret experience, and the goal of the workshop is never just ‘trauma recovery’.

The definition of trauma is not as simple as we think, and it may vary with both culture and era. Some people wonder whether Holotropic Breathwork might be re-traumatising; many people wonder whether any technique in which trauma is revisited is re-traumatising. Grof’s belief, however, is that the trauma only manifests in a holotropic session if it is necessary for healing. Holotropic Breathwork facilitators would never insist that someone work on a trauma, nor determine how long one should work on a trauma.

It is possible for people who are working through trauma (via any modality) to get stuck in that process for a while. Indeed, it seems that this is one way in which some people move forward: They get stuck in a particular perspective until they get so fed up with being stuck in that perspective that a new one breaks through. During the period of stuckness, however, they can certainly seem to be caught in a loop.

But it is important to remember that Holotropic Breathwork, because it is not about trauma recovery, is always offering clients a new way out of old problems. The primary injunction in Holotropic Breathwork is not ‘go into the trauma’ but ‘do the breathing until you are surprised by what emerges’. In other words: ‘don’t get stuck in your assumptions.’

Quite frankly, I have seen more re-traumatisation by therapists and gurus who impose their own assumptions on the wide-open psyche of their clients—interpreting symptoms according to their particular model, advising them to do particular forms of work, managing their life choices, etc. Holotropic Breathwork is simply a loving field in which whatever needs to emerge can do so.

In many countries, Holotropic Breathwork is actually seen more as a spiritual process than a therapeutic one; workshops attract people who are primarily looking to expand their awareness. But whether the benefits of a Holotropic Breathwork are spiritual or therapeutic (and I’m not really sure there is a difference), the main point is that what happens in a Holotropic Breathwork session, at its simplest, is this: you get the next part of the picture[iv].

12. Does Holotropic Breathwork go too deep?

First, there is no question that Holotropic Breathwork allows people to have deep experiences, and to some extent, it catalyzes these experiences. Remember that the client is always in control of the mechanism that drives the depth of the process: breathing. No one is forced to go deeper than he wishes.

As with osteopathy and homeopathy—and to some extent, Jungian analysis—in Holotropic Breathwork, symptoms are expected to get bigger—or be amplified—as a means of resolution: this is called a ‘healing crisis’. This is quite different from the medical model, where the elimination of symptoms—sometimes without anyone even knowing the cause—is often standard.

Grof believes that a symptom is like an interference pattern—it represents the ‘edge’ of another reality or gestalt that is trying to emerge.[v] The problem is that that other reality doesn’t match this reality very well. For example, a panic attack might be the psyche’s attempt to heal an earlier trauma; it certainly has many features of a birth process (claustrophobia, constriction, fear, elevated heart rate, etc.). The problem, therefore, is not the panic attack, but the context in which it is happening. If it happens when you’re driving a car, or sitting at your desk in the office, it is considered pathological. But if it happens in a safe and supportive environment, where it is possible to experience it fully, then underlying gestalt can be resolved, and it is considered healing. In a world where the dominant model of healing encourages the suppression symptoms, it’s not surprising that any technique that encourages the amplification of symptoms will be controversial.

I have certainly seen people get into some very challenging territory in Holotropic Breathwork sessions, but they might well have got into even more difficult situations had those energies erupted in ordinary life. At intensive times of change in one’s life there can be mood swings, active dreams, and deep anxiety. Many people come to a Holotropic Breathwork workshop during such periods of transformation; therefore it may appear to a casual observer that Holotropic Breathwork has caused this unsettlement, rather than being a method of processing it.

Many come to Holotropic Breathwork as a last resort. I have worked with many clients who were in recovery from abuse by the psychiatric profession, or from manipulative shamans or yogis, and who only found a safe, non-judgemental space in a Holotropic Breathwork workshop. I have also worked with many people who were in recovery from the abuse of psychedelics, which can create a very complex and challenging psychological state. It is not surprising that Holotropic Breathwork attracts such people, for the safety, depth, and respect for the client that it offers. But it would be a mistake to believe that Holotropic Breathwork induces a difficult experience in people who would not otherwise encountered it. My general experience is that people find that they can resolve issues in a Holotropic Breathwork session that they just couldn’t resolve anywhere else.

I am not denying that Holotropic Breathwork a deep, and at times emotional, process. But deep experiences are not always painful or dark (though these do seem to get the most press). I have seen many people, in a Holotropic Breathwork workshop, liberate their ability to laugh deeply, learn to cry profoundly, move parts of their bodies that have been frozen for years, experience ecstasy for the first time, and find a quietness and peace that they have never touched in ordinary life.

Conclusion

Finally, one of the most common misperceptions about Holotropic Breathwork, to my mind, is one that Grof himself, and many trained facilitators, are guilty of advancing. They have described this technique primarily as a way to experience a non-ordinary state of consciousness safely. That’s a very attractive proposition to some people, but it misses many of the other reasons to participate in a workshop, and does not describe very accurately what most people experience as the main benefits of a workshop.

In a Holotropic Breathwork workshop, people experience a place of deep safety and profound trust, often for the first time. They learn to take time out from ordinary life for their deeper concerns and dreams. They learn how to bear witness to their own suffering and the suffering of others. They learn how to support one another through a dramatic process of unfolding. They learn that the enormous spiritual treasures of the Kosmos are available in each of us. They learn to trust their inner healer. They learn that experiencing their truth is the quickest way to wholeness. They learn to be compassionate to themselves and others. They learn to celebrate their uniqueness and respect other peoples’ differences. They learn that it’s okay to feel little and vulnerable, and that it’s okay to feel big and powerful. They learn to empathize with everything in the created universe as part of themselves, and they learn that they too are part of everything. They learn how to trust the deep wisdom of their own psyche, and to stay open to its ever-evolving story.

———————————–

Martin Boroson is the author of One-Moment Meditation: Stillness for People on the Go, and the interfaith creation story, Becoming Me, based on his holotropic experiences. He ran Holotropic Breathwork workshops in Ireland for ten years with the Transpersonal Group, and is currently President of the Stanislav and Christina Grof Foundation. He delivers keynotes and workforce training to corporations and hospitals on the benefits of meditation for leadership and resilience, and can be reached at www.martinboroson.com.

Jean Farrell, Nienke Merbis, and Dara White are Grof-certified facilitators who run regular workshops in Ireland. They can be reached at www.breathingtime.ie.

More information about Holotropic Breathwork, including research into its effectiveness, can be found from the Association for Holotropic Breathwork International website at www.ahbi.org. A list of certified facilitators is available by email from GTT through their website – www.holotropic.com.

[i] Grof, S. (1992) The Holotropic Mind. New York:Harper Collins, p 23.

[ii] Boroson, Martin, (1998) ‘Radar to the Infinite: Holotropic Breathwork and the Integral Vision’ reprinted in K. Taylor (ed), Exploring Holotropic Breathwork: Selected Articles from a Decade of The Inner Door. Santa Cruz: Handford Mead, 2003.

[iii] Grof, S. (1985) Beyond the Brain: Birth, Death and Transcendence in Psychotherapy, Albany: State University of New York, pp. 267 – 268. See also Sparks, T., The Wide Open Door, and Grof, C., The Thirst for Wholeness.

[iv] Boroson, M., ibid.

[v] Grof, S., (1992), p. 206.

About EMDR :

From EMDR.com

For Clinicians:

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is a psychotherapy treatment that was originally designed to alleviate the distress associated with traumatic memories (Shapiro, 1989a, 1989b). Shapiro’s (2001) Adaptive Information Processing model posits that EMDR therapy facilitates the accessing and processing of traumatic memories and other adverse life experience to bring these to an adaptive resolution. After successful treatment with EMDR therapy, affective distress is relieved, negative beliefs are reformulated, and physiological arousal is reduced. During EMDR therapy the client attends to emotionally disturbing material in brief sequential doses while simultaneously focusing on an external stimulus. Therapist directed lateral eye movements are the most commonly used external stimulus but a variety of other stimuli including hand-tapping and audio stimulation are often used (Shapiro, 1991). Shapiro (1995, 2001) hypothesizes that EMDR therapy facilitates the accessing of the traumatic memory network, so that information processing is enhanced, with new associations forged between the traumatic memory and more adaptive memories or information. These new associations are thought to result in complete information processing, new learning, elimination of emotional distress, and development of cognitive insights. EMDR therapy uses a three pronged protocol: (1) the past events that have laid the groundwork for dysfunction are processed, forging new associative links with adaptive information; (2) the current circumstances that elicit distress are targeted, and internal and external triggers are desensitized; (3) imaginal templates of future events are incorporated, to assist the client in acquiring the skills needed for adaptive functioning.

For Laypeople:

EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) is a psychotherapy that enables people to heal from the symptoms and emotional distress that are the result of disturbing life experiences. Repeated studies show that by using EMDR therapy people can experience the benefits of psychotherapy that once took years to make a difference. It is widely assumed that severe emotional pain requires a long time to heal. EMDR therapy shows that the mind can in fact heal from psychological trauma much as the body recovers from physical trauma. When you cut your hand, your body works to close the wound. If a foreign object or repeated injury irritates the wound, it festers and causes pain. Once the block is removed, healing resumes. EMDR therapy demonstrates that a similar sequence of events occurs with mental processes. The brain’s information processing system naturally moves toward mental health. If the system is blocked or imbalanced by the impact of a disturbing event, the emotional wound festers and can cause intense suffering. Once the block is removed, healing resumes. Using the detailed protocols and procedures learned in EMDR therapy training sessions, clinicians help clients activate their natural healing processes.

More than 30 positive controlled outcome studies have been done on EMDR therapy. Some of the studies show that 84%-90% of single-trauma victims no longer have post-traumatic stress disorder after only three 90-minute sessions. Another study, funded by the HMO Kaiser Permanente, found that 100% of the single-trauma victims and 77% of multiple trauma victims no longer were diagnosed with PTSD after only six 50-minute sessions. In another study, 77% of combat veterans were free of PTSD in 12 sessions. There has been so much research on EMDR therapy that it is now recognized as an effective form of treatment for trauma and other disturbing experiences by organizations such as the American Psychiatric Association, the World Health Organization and the Department of Defense. Given the worldwide recognition as an effective treatment of trauma, you can easily see how EMDR therapy would be effective in treating the “everyday” memories that are the reason people have low self-esteem, feelings of powerlessness, and all the myriad problems that bring them in for therapy. Over 100,000 clinicians throughout the world use the therapy. Millions of people have been treated successfully over the past 25 years.

EMDR therapy is an eight-phase treatment. Eye movements (or other bilateral stimulation) are used during one part of the session. After the clinician has determined which memory to target first, he asks the client to hold different aspects of that event or thought in mind and to use his eyes to track the therapist’s hand as it moves back and forth across the client’s field of vision. As this happens, for reasons believed by a Harvard researcher to be connected with the biological mechanisms involved in Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep, internal associations arise and the clients begin to process the memory and disturbing feelings. In successful EMDR therapy, the meaning of painful events is transformed on an emotional level. For instance, a rape victim shifts from feeling horror and self-disgust to holding the firm belief that, “I survived it and I am strong.” Unlike talk therapy, the insights clients gain in EMDR therapy result not so much from clinician interpretation, but from the client’s own accelerated intellectual and emotional processes. The net effect is that clients conclude EMDR therapy feeling empowered by the very experiences that once debased them. Their wounds have not just closed, they have transformed. As a natural outcome of the EMDR therapeutic process, the clients’ thoughts, feelings and behavior are all robust indicators of emotional health and resolution—all without speaking in detail or doing homework used in other therapies.

Treatment Description:

EMDR therapy combines different elements to maximize treatment effects. A full description of the theory, sequence of treatment, and research on protocols and active mechanisms can be found in F. Shapiro (2001) Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Basic principles, protocols and procedures (2nd edition) New York: Guilford Press.

EMDR therapy involves attention to three time periods: the past, present, and future. Focus is given to past disturbing memories and related events. Also, it is given to current situations that cause distress, and to developing the skills and attitudes needed for positive future actions. With EMDR therapy, these items are addressed using an eight-phase treatment approach.

Phase 1: The first phase is a history-taking session(s). The therapist assesses the client’s readiness and develops a treatment plan. Client and therapist identify possible targets for EMDR processing. These include distressing memories and current situations that cause emotional distress. Other targets may include related incidents in the past. Emphasis is placed on the development of specific skills and behaviors that will be needed by the client in future situations.

Initial EMDR processing may be directed to childhood events rather than to adult onset stressors or the identified critical incident if the client had a problematic childhood. Clients generally gain insight on their situations, the emotional distress resolves and they start to change their behaviors. The length of treatment depends upon the number of traumas and the age of PTSD onset. Generally, those with single event adult onset trauma can be successfully treated in under 5 hours. Multiple trauma victims may require a longer treatment time.

Phase 2: During the second phase of treatment, the therapist ensures that the client has several different ways of handling emotional distress. The therapist may teach the client a variety of imagery and stress reduction techniques the client can use during and between sessions. A goal of EMDR therapy is to produce rapid and effective change while the client maintains equilibrium during and between sessions.

Phases 3-6: In phases three to six, a target is identified and processed using EMDR therapy procedures. These involve the client identifying three things:

1. The vivid visual image related to the memory

2. A negative belief about self

3. Related emotions and body sensations.

In addition, the client identifies a positive belief. The therapist helps the client rate the positive belief as well as the intensity of the negative emotions. After this, the client is instructed to focus on the image, negative thought, and body sensations while simultaneously engaging in EMDR processing using sets of bilateral stimulation. These sets may include eye movements, taps, or tones. The type and length of these sets is different for each client. At this point, the EMDR client is instructed to just notice whatever spontaneously happens.

After each set of stimulation, the clinician instructs the client to let his/her mind go blank and to notice whatever thought, feeling, image, memory, or sensation comes to mind. Depending upon the client’s report, the clinician will choose the next focus of attention. These repeated sets with directed focused attention occur numerous times throughout the session. If the client becomes distressed or has difficulty in progressing, the therapist follows established procedures to help the client get back on track.

When the client reports no distress related to the targeted memory, (s)he is asked to think of the preferred positive belief that was identified at the beginning of the session. At this time, the client may adjust the positive belief if necessary, and then focus on it during the next set of distressing events.

Phase 7: In phase seven, closure, the therapist asks the client to keep a log during the week. The log should document any related material that may arise. It serves to remind the client of the self-calming activities that were mastered in phase two.

Phase 8: The next session begins with phase eight. Phase eight consists of examining the progress made thus far. The EMDR treatment processes all related historical events, current incidents that elicit distress, and future events that will require different responses

Transpersonal psychology

Transpersonal psychology is a sub-field or “school” of psychology that integrates the spiritual and transcendent aspects of the human experience with the framework of modern psychology. It is also possible to define it as a “spiritual psychology”. The transpersonal is defined as “experiences in which the sense of identity or self extends beyond (trans) the individual or personal to encompass wider aspects of humankind, life, psyche or cosmos”.[1] It has also been defined as “development beyond conventional, personal or individual levels”.[2]

Issues considered in transpersonal psychology include spiritual self-development, self beyond the ego, peak experiences, mystical experiences, systemic trance, spiritual crises, spiritual evolution, religious conversion, altered states of consciousness, spiritual practices, and other sublime and/or unusually expanded experiences of living. The discipline attempts to describe and integrate spiritual experience within modern psychological theory and to formulate new theory to encompass such experience.

Transpersonal psychology has made several contributions to the academic field, and the studies of human development, consciousness and spirituality.[3][4] Transpersonal psychology has also made contributions to the fields of psychotherapy[5] and psychiatry.[6][7]

Contents

- 1 Definition

- 2 Development of the academic field

- 3 Branches and related fields

- 4 Research, theory and clinical aspects

- 5 Organizations, publications and locations

- 6 Reception and criticism